March 16, 2018: The Great Slowdown

Welcome to Signal Problems, a weekly newsletter helping you figure out what is going on with the subway. I’m Aaron Gordon, a freelancer writing about many subjects, one of which is transit for the Village Voice. If you’re a new or prospective subscriber, head over to the Subway Knowledge Base page for an introduction to the state of the subway.

As always, send any feedback, subway questions, and Dog in a Bag photos to aaron.wittes.gordon@gmail.com. I’d love to hear from you. As someone on a stalled Q train once told me, we’re all in this together.

1,355.

That is the number of delayed trains per weekday attributed to “insufficient capacity, excess dwell, unknown” in December 2017. That’s about one out of every six trains. Keep that number in mind as I throw out some other delay totals from that month:

Signals: 227

Track: 122

Car equipment: 70

Sick/Injured customer: 121

Power/Utility: 0

The first time I saw this data, I couldn’t believe it. Surely, I was missing something.

As I wrote in my investigation that was published this week (if you haven’t read it yet, please do as the rest of this section might not make much sense otherwise) there wasn’t some sudden explosion in delays to which the MTA failed to sufficiently react. This was a gradual, elongated process, one that unfolded over years, if not decades.

And nobody did anything about it. They just watched it get worse and worse and worse. Until the subway “crisis.”

Over the last month or so, as I have become privy to new information, I came to realize the subway crisis of 2017 was more or less invisible in the subway’s performance data. Which is to say, the subway kept getting worse at about the same rate it had been getting worse for years. Instead, to use a rather unpleasant analogy, we were the frogs in the pot as the water boiled. It wasn’t until we saw the bubbles that we realized it was getting awfully hot in here.

The MTA’s reaction to all this was less than exemplary. First, they blamed riders because there were too many of us. Then they blamed Con Ed, even though, as you can see above, power delays are few and far between. Finally, they launched the Subway Action Plan, which acknowledged a problem, but not the problem. It was all due to external forces, they said: increased ridership, budget cuts, and deferred maintenance. Not our fault. It is an $836 million policy whose main metric of success is reduced bad headlines, not delays.

The truth, as I found in my investigation, is perhaps the most galling revelation one could possibly imagine. They’ve just been slowing the trains down, often times intentionally, sometimes due general operational inefficiency. It’s impossible to apportion those causes accurately based on their current data capture methods. But we know the signal modifications are at the very least a very big problem.

Nevertheless, they didn’t heed warning signs, they didn’t care to investigate, and nobody, apparently, felt empowered to do anything about it. They greeted the delay figures with little more than a shrug.

When I became aware of all of this, as a reporter I was singularly focused on getting as much accurate information as I could, vetting it through multiple sources, and publishing a story that would help the public understand the misdirection campaign to which the MTA has subjected us over many years.

But as a person who grew up in the tri-state area; whose earliest memory of true independence as a young teenager was taking Metro North into Grand Central and then hopping on the 4 to Yankee Stadium by myself; for whom the subway was a symbol of autonomy and possibilities; I was flabbergasted. How could the people running this agency not comprehend the immense responsibility they had to almost six million New Yorkers every day? How could they have such little regard for public service that they couldn’t take one minute every month to look at the actual data about how the system is running? How could they not feel a burning responsibility to fix this festering issue? How could this happen?

Regardless, it did happen, and it’s cost us all dearly. Every day. The lost hours of paid work, the missed doctor appointments, job interviews, classes, day care pick-ups, dinners, movies, time spent with loved ones. The increased anxiety, stress, and angst that comes from never knowing if this commute will take half an hour or two hours.

No single decision, signature on the dotted line, or policy change got us here. It’s important to remember that. This was years and years of institutional rot. To return to my cruel analogy, even we could turn the heat off, the water still has to cool.

This Week In #CuomosMTA

A week ago, the MTA unveiled the winners to Cuomo’s much-touted Genius Challenge, “an international competition seeking innovative solutions to modernize and improve the reliability of the New York City subway system.” Eight winners split a total prize pool of $2.5 million. Some of the ideas are promising enough, like modular train cars that don’t have to last 50 years and receive expensive mid-life overhauls, and others were not. Here are two good posts about the winners and the contest in general if you’d like to learn more.

(My biggest takeaway from the Genius Challenge was that while four MTA senior executives were judging a global competition to improve the subway my sources who actually work for the MTA felt so discouraged by their inability to be heard that they leaked documents to the press. Their genius idea: speed the trains back up again. It should have won.)

The idea that got the most attention—and ridicule—was the proposal to extend the length of trains beyond what the platforms allow. The middle cars would platform at every stop, while the four cars on either end would alternate stops. So passengers would have to make sure they get on a car that will platform at their stop. (If you’ve ever been on Metro North or LIRR or some Amtrak trains where some cars don’t platform, you know what a tremendous hassle this can be for the uninitiated; the ticket checkers literally have to tell every single person to move cars.) The low-end cost estimate for this plan is somewhere in the area of $12 billion (yes, with a B), thanks mostly to new cars and digital signage. The person behind this idea that will (lord willing) get quietly entered into the dustbin of history pocketed $330,000 in prize money, or the equivalent of 227 years’ worth of unlimited metrocards.

As for the contest as a whole, I think Alon Levy summed it up nicely:

Cuomo attempted to inject the inventions of the American tech industry into the subway. Instead, he created space for cranks to promulgate their ideas and for vendors to have a leg up over their competitors in any future bid.

News You Probably Can't Use, But About Which You Can Certainly Brood

The federal government has joined a lawsuit against the MTA for failing to include elevators and other ADA-required accessibility upgrades in station renovations. That specific lawsuit is limited to a station in the Bronx, but it is likely to set a precedent for others. The MTA has refused to do so much as open previously-closed staircases at stations for years claiming they can’t do so without making the entire station ADA-compliant (the horror!). Which is to say, there’s been an ADA reckoning for the MTA coming down the pipe for some time.

The MTA hired Sarah Meyer from the PR firm Edelman to be the new "Chief Customer Officer” in charge of improving communications. She has been consulting for the MTA since August but this seems like a very Byford-y hire. It sounds like her first initiative during big meltdown was to have the NYCTSubway account send out apologetic tweets.

(1) We faced significant challenges during tonight's rush hour. Three individuals were struck by trains on the R, 7 and D lines respectively, and there was a defective piece of equipment at Bergen St that shut down our signaling system for the F and G trains.

March 16, 2018

(2) For those impacted, we know your commute was incredibly frustrating and apologize for letting you down. Please know that we will be launching a full internal investigation of the signal malfunction, so that we identify the root cause to prevent it from happening again

March 16, 2018The LIRR is taking a page out of Transit’s playbook, blaming a quarter of all late, canceled, and terminated trains on its customers. I’d really, really love to know how they manage to blame canceled trains on customers.

The MTA had its bond rating lowered by S&P due to the amount of money it’s spending on labor and debt service (but mostly debt service). And Moody’s thinks when the next recession hits, the MTA (and therefore we) will be screwed. I mean, that’s the nature of recessions, right? Everybody’s screwed?

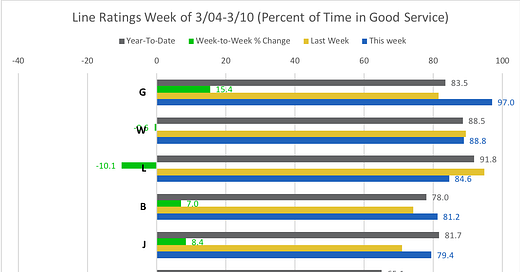

Line Ratings

Using the fantastic Subwaystats.com website, I've compiled weekly ratings for each line. Each number represents the percent of time the last week (Monday-to-Sunday) that the line had "Good Service." For example, if the number is 70 percent, that means the line had "Good Service" 70 percent of the time and any form of disruption—planned work, delays, service changes, etc.—the other 30 percent.

This is just one of many ways to measure a line's performance. It's not perfect. For one, it relies on the MTA's definition of "Good Service," which there are very good reasons to doubt. On top of that, most people would prefer a line be down all weekend for planned maintenance but not for the two hours during rush hour. I wish the MTA compiled Lost Customer Hours like Transport for London does, but then again I wish the MTA did a lot of things.

If you’re having trouble viewing the graph below in the email, check it out in your browser by clicking the “view in browser” button at the top-right of this email or going to signalproblems.substack.com.

In Which I Make An Educated Guess About When Things Will Get Better

This week's estimate: 2024

A bureaucracy that looked the other way as its service deteriorated for years doesn’t turn around very quickly, if at all. We’re in for the long haul.

Prove me wrong, MTA. Prove me wrong.

Your Upcoming Service Advisories, Provided by Lance from Subway Weekender

Weekend

4 - Uptown service is local-only in Manhattan (Sunday only)

6 - Pelham Bay-bound service is express-only between 3 Avenue and Parkchester

A - No service between 181 Street and 207 Street

A C - Uptown service is express-only between 59 St-Columbus Circle and 168 Street

F - No service between Church Av and Coney Island

J - No service between Hewes St and Broad St

M - No mainline service between Broadway Junction and Essex St

N - No service between Times Sq-42 Street and Ditmars Blvd

Q - All service is local-only in Manhattan

R - All service runs via 63rd Street

Nights

4 - No service between 149 St-Grand Concourse and 125 Street

4 6 - Downtown service is express-only between 125 Street and Grand Central

D F - Brooklyn flip-flop between W 4 Street and Coney Island

E - Jamaica Ctr.-bound service is express-only between Roosevelt Av and Jamaica-Van Wyck

G - No service between Bedford-Nostrand Avs and Court Sq

N - multiple diversions

No service between Queensboro Plaza and Times Sq-42 Street

Manhattan-bound service runs via Q line between DeKalb Av and Canal St

R - multiple diversions

No service between Atlantic Av and Whitehall St

All service is express-only between Atlantic Av and 36 St/4 Av

Subway Detective Agency

Have a weird question about the subway you’ve always wanted to know? Send it to aaron.wittes.gordon@gmail.com.

I am going to cheat this week and answer my own question to make a larger point relating to my article that published this week. Why does the southbound Q almost always stop on the Manhattan Bridge?

Before southbound B/Q trains get from the bridge to Dekalb, they have to go through the Gold Street interlocking, a complex web of tracks that turns the fairly basic four-track layout on the bridge into, well, this:

Gold Street is a very old interlocking—I don’t believe it’s been renovated since the 1950s—and almost nothing that happens here is automatic. When a train approaches the interlocking, it radios to the dispatcher with its line and route info (the tower operator can also see the train on a CCTV monitor). The tower then manually flips switches to get the track in place for the proper route, and then the signal clears and the train can go. All that takes time, so usually the train approaching from the bridge has to wait (or at the very least slow) before the signal clears.

Now: in my investigation, I quoted an anonymous train operator who has been doing this since the 1980s:

“If we were delayed by something like a sick passenger or a signal problem, obviously I would know,” the train operator who spoke to the Voice said. “But usually I’m late because of many smaller problems.”

Sometimes, he says, his train will get to a junction point with another line on schedule but will have to wait for a train that’s running late to pass in front of him; other times, a conductor slow to close the train doors will result in the train dwelling longer than it should, or he’ll be stuck at a station trying to speak to a dispatcher on the MTA’s balky radio system. On certain lines, he says, “I’m always late because the grade time signals slow me down, but the schedule doesn’t provide enough running time for me to make the trip on time.”

Gold Street is a great example of how these little things can compound to create a big delay. The schedule, such as it is written on paper, is calculated down to 30 second intervals so that trains don’t arrive at junctions simultaneously. But it’s easy to see how if a bunch of trains are going slower than scheduled it will create a traffic jam at major interlockings like this one. Ever been on a southbound B/Q and have it lurch forward about 750 feet at a time on the bridge four or five times before getting to Dekalb? That’s a traffic jam at the interlocking, a five minute delay, and a late train.

Another issue few people want to really get into, but nevertheless matters, is the competency of the tower operator in charge of the switches. By no means am I implying all tower operators are incompetent. But, like any skilled position, some are more experienced and/or capable than others. Traffic will run smoother when a more skilled tower operator is working, and less so otherwise.

So while my article focused on the timers because they’re the most important, obvious, and proved example, there are a lot of little things that contribute to the overall problem of operations simply not being as smooth as they used to be. It’s due to a general de-emphasis of efficiency and speed. It’s a complicated problem of bureaucratic rot. The timers may have a fairly easy answer, but all the other little things will be much more challenging to address.

MTA Mention of the Week

The subway conductor literally just told us all that “at this present time I do not know where this train will be terminating service, I’ll let you know when I do”

There’s a first time for everything in New York

I Was on the TV

Corrections

I got the way CBTC works slightly backwards in last week’s edition. The trains have the transponders which communicate with trackside radios. The RFID chips are trackside which help the train recognize where it is on the track. For a more detailed explanation, see this thread. Apologies for the error.

Dog in a Bag

Have a dog in a bag photo? Reading this on the subway and see a dog in a bag? Take a picture and send it to aaron.wittes.gordon@gmail.com.

Photo credit: Samantha Green

Photo credit: Samantha Green

Hey, since you made it all the way to the end, you may be enjoying this newsletter. If so, please help spread the word, perhaps by using the nifty sharing buttons below or telling a few friends using out-loud words. A lot of work goes into making this newsletter every week. Sharing it with others who might enjoy it too is the best way you can say thanks.